Yes.

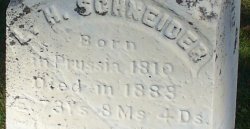

Wheatland Cemetery

Many contemporary documents–ships’ lists, Census records, even grave markers–give “Prussia” as the place of origin of our people from Wunderthausen and elsewhere. This has often led the naive astray into thinking they were “Russian” or maybe from Berlin. As of 1947, Prussia as a place no longer existed.

Most narrowly, (Brandenburg) Prussia was a state in eastern Germany with its capital in Berlin but at times stretching hundreds of miles further east. It rose to become a relatively-great power among the European states by the time of Napoleon. After the final defeat of the French, the major German states divvied up the small ones and what had been the tiny but independent Counties of Wittgenstein were absorbed into greater Prussia. This map shows the extent of the Prussian state with the Rhine Province (now including Wittgenstein) in red. Here is a similar map for Pomerania.

Thus from 1816 forward, the Wittgensteiners (and Pomeranians and many others) were legally citizen-subjects of the King of Prussia. Of course they were ethnically German but in terms of political identity they were Prussian. By 1871, Prussia had merged all of what we think of as Germany into a single state known as the German Empire. The tragedies of the 20th century need not be recounted here.

In German, the state’s name was Preußen (pronounced Proy’ – sen). A Prussian was a Preuß.

The Wikipedia article, as always, is rich: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prussia

Where some acquaintances get “Rye-diesel” I don’t know, and I try not shudder. I mean, there is a place for bio-fuels but they were not part of our heritage.

Where some acquaintances get “Rye-diesel” I don’t know, and I try not shudder. I mean, there is a place for bio-fuels but they were not part of our heritage.